Officers' Lyceums:

Professional Military Education in the Nineteenth-century

Background

Following the Civil War, the mass volunteer armies that fought the war were quickly disbanded, and within a few years the entire Regular Army shrank below 25,000 troops and rapidly transitioned back into a frontier constabulary. Yet the middle and senior officer ranks remained dominated by those who had held high rank and responsibility during the war, while the junior ranks were increasingly the exclusive province of graduates of the United States Military Academy at West Point.

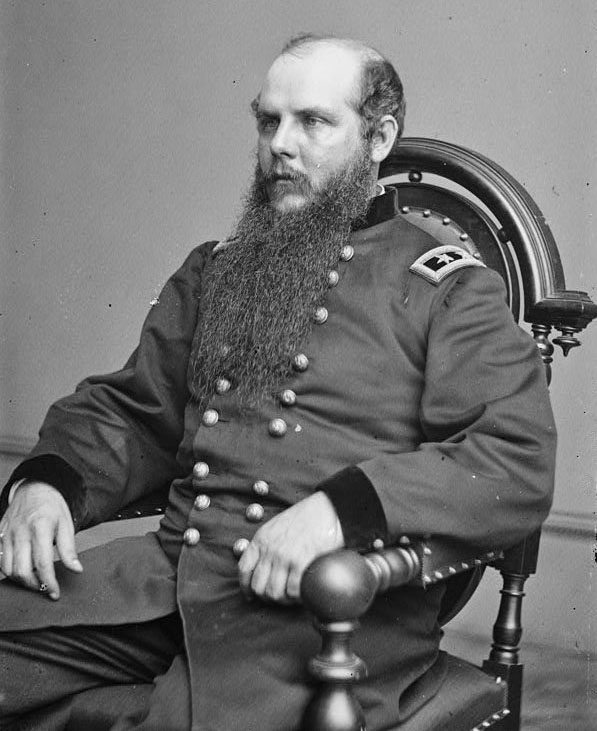

John M. Schofield, Commanding General of the Army

The Lyceum Program

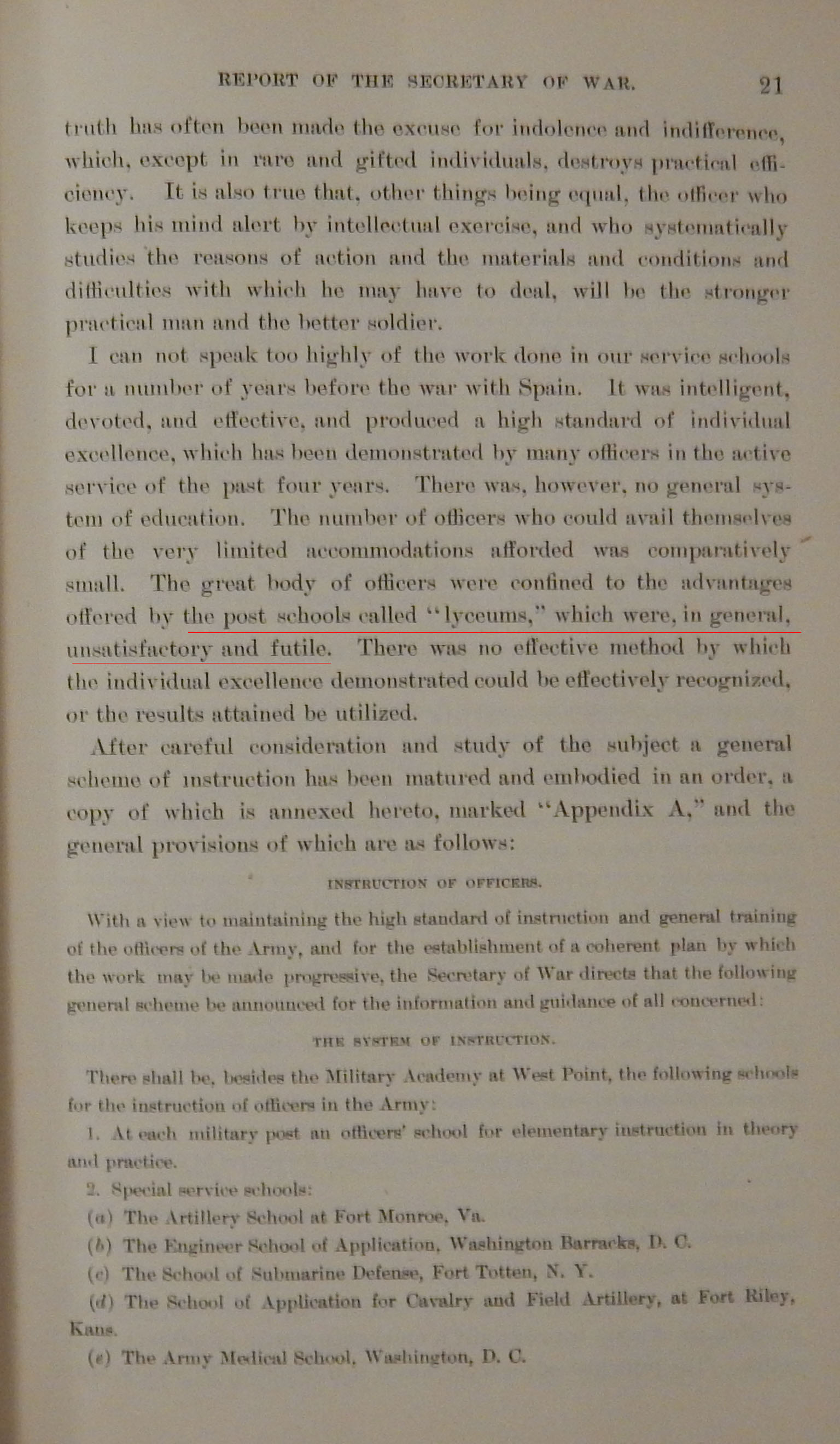

As part of this movement towards professionalization and a systematic education for officers, General John M. Schofield, the Commanding General of the Army, in 1891 issued War Department General Order 80 calling for the formation of Officers’ Lyceums at each Army post. Combining lectures, recitals, discussions, and the writing and presentation of papers on professional topics, each Lyceum would form the focal point of continuous professional education at the Army posts spread across the frontier. The Lyceums provided both a mechanism to inculcate the wider officer corps in this ethos of professionalization and a venue in which to articulate the ideals of Army reformersWhile the program faced significant challenges in its execution and experienced a wide variance of effectiveness and participation, at certain moments and at certain posts it embodied most of the larger intents and elements of the movement for professionalization that swept the Army officer corps in the period between the end of the Civil War and the turn of the century. Despite Secretary Root’s evaluation of the program as “unsatisfactory and futile,”1United States War Department, Annual Reports of the War Department for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1901, Vol. 1, Part 1 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1901), 20. the Officers’ Lyceum program represented a critical component in the progressive effort of Army officers to professionalize and modernize their institutions. The Lyceums provided both a mechanism to inculcate the wider officer corps in this ethos of professionalization and a venue in which to articulate the ideals of Army reformers, ideals that predated and indeed provided much of the framework emplaced by Root at the outset of the twentieth century. The Officers’ Lyceums, then, represented both a critical element of professional education in the late nineteenth century Army as well as a manifestation of the professional spirit that began to animate the officer corps during this period, a spirit that would eventually help transform the small frontier constabulary army of the nineteenth century into the modern, professional fighting force of the twentieth century.

the Officers’ Lyceum program represented a critical component in the progressive effort of Army officers to professionalize and modernize their institutions. The Lyceums provided both a mechanism to inculcate the wider officer corps in this ethos of professionalization and a venue in which to articulate the ideals of Army reformers, ideals that predated and indeed provided much of the framework emplaced by Root at the outset of the twentieth century. The Officers’ Lyceums, then, represented both a critical element of professional education in the late nineteenth century Army as well as a manifestation of the professional spirit that began to animate the officer corps during this period, a spirit that would eventually help transform the small frontier constabulary army of the nineteenth century into the modern, professional fighting force of the twentieth century.